Robin Williams died yesterday, killed in what was reported as a suicide. My breath caught when I heard, but I made a small mental readjustment and thought, “Nah, it’ll be like all the other fake celebrity deaths; I’ll go on eating my burrito.”

When later the Responsible Media (TM) started reporting it, I deflated. I don’t think I was the only one to shrink a little; my social media was swamped with tributes, statements of sadness, and memories of Robin Williams and his work. It was filled with something else, too: a counter-reaction.

There was a collection of people who lamented that there was so much attention being paid to the suicide of one druggie comedian instead of some other major world event, like poverty, Gaza, ISIS, police brutality, etc. I actually think theirs is a reasonable reaction, as the loss of one man cannot be equivalent to the loss of scores of people, so let me explain why I think my sadness at William’s death is just as reasonable.

In a nutshell, Robin Williams was like a friend, who popped into and out of my life with each movie, routine, and painful story of drug use or loss that I saw or read about. If I lost a loved one, a cousin, sibling, or parent, no one would question my right to grieve, because we know that I “know” them, they were in my life and I in theirs. The loss of Williams is obviously less, since he was a performer and I was a stranger to him, but like most of my favorite authors, musicians, and artists, he was no stranger to me.

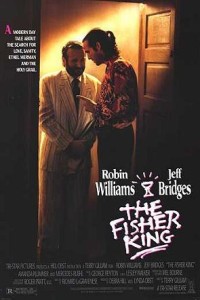

Many of my friends in stand-up have been able to meet and get to know Robin Williams, something I’ll sadly not be able to do. Even without that secondary personal connection, though, his movies mirrored my emotional development. I was a kid when he made Aladdin, I was a student when he made Good Will Hunting, and I knew grief when he made The Fisher King. With his passing, I feel like I lost an reliable emotional touchstone, like an old restaurant in your hometown that has somehow stayed in business decades longer than it should have. Was he a friend of mine? No, he was not, but he was there when I made friends, and when I lost them.

With a celebrity like Williams dies, it is easy to dismiss the crass celebrity culture that exists in the US, which celebrates the trite, the superficial, and the pretty over the deep and meaningful. The news cycle should have more substance and less style, more analysis and less Hollywood gossip; this is a totally valid, and damning, critique on modern celebrity culture. In the case of Robin Williams, though, feeling less bad about his death does not mean we would feel more bad about the loss of civilians in a civil conflict; I’d argue that becoming more callous about the loss of anyone, even just some actor, just gives us a little more practice in the art of callousness.

If we intend to be more empathetic with strangers across the world and in our own hometowns, the solution is not to ridicule people who feel emotional about the loss of a famous celebrity; it is to give us more reason to feel the loss of the non-famous, the anonymous.

When Robin Williams died, we saw a person who made us laugh, an actor who could make us cry, and the face of a loneliness and depression that far, far too many of us confront in the dark, alone. We know that face, we see in our family, in our friends, and in our mirror.

If we want more of us to feel the loss of the family in Aleppo shelled by mortar fire, or the baby in the hospital in Gaza who died from a rocket attack, or the young man caught in a Molotov cocktail attack on his synagogue in Frankfurt, then we have to tell their stories, too. Don’t simply pass on a news report about a nameless, faceless refugee camp; find one of them and tell me her name, tell me his dreams. Tell me what they wanted out of life before the men with guns came, before their home became a war zone. Tell me how they lived before they died.

Sawssan Abdelwahab, who fled Idlib in Syria, walks with her children outside a refugee camp near the Turkish-Syrian border. (Photo: REUTERS/Zohra Bensemra)

“500 dead” is just a number, a collection of bodies. We are not just bodies, we are the souls and hopes and dreams that live in those bodies until the moment our hearts stop. We know what Robin Williams looked like when his heart was beating; we know how he smiled and we know how he spoke. Can we try to say the same for the Tsunami victim? For the flood victim?

Don’t get me wrong; we should care about the dozen that died from X, and the thousand that are fleeing for safety in Y, even if we don’t know their stories. But if we know their stories, then we are not just mourning a number, we are mourning a person, a person that could have been our friend, a person that could have been us.

People will shed their tears for strangers, but they will shed their blood for their friends. We should give the unnamed names, put faces on the faceless, because that is the only way we can start to see the friends we have, hidden in the numbers.

—

12 Aug 2014

by Mark Nabong

2 Responses to Tragedies and Statistics